Together we were building a new world. Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel and their avant-garde circle

Fictional Interview with the Artists Ella Bergmann-Michel (EBM) and Robert Michel (RM) by Michael Honecker (MH)

MH : Dear Ella Bergmann, dear Robert Michel, I’m delighted to be with you today and very glad that we can take this opportunity to talk about your pre-war life and the deepest artistic friendships you formed during that time.

RM : Yes, we are granting you and the gallery a privilege by allowing you to interview us today. Depending on my mood, I occasionally receive art dealers and gallerists, but usually, when they dare to come here, I shout “nobody’s home” through a small window in the mill, and ask them to leave and come back later at a more suitable time.

MH (laughs and thanks them once again): Let’s begin, if you don’t mind, with the oldest of your friendships which is, of course, the one between the two of you. When and how did you meet and fall in love?

EBM : For that, I have to go back in time. I wanted to become an artist from a very young age and, in addition to a musical education, I started taking painting classes early on in my hometown of Paderborn and later in Magdeburg. However, I knew that my father and stepmother would never have allowed me to leave home to study fine arts. So I resorted to a trick and misled my parents by pretending I was going to Weimar, 250 kilometers from Paderborn, to study music. As soon as I arrived, I enrolled in the Saxon Grand-Ducal School of Art, in Walther Klemm’s drawing class. Back then in 1915, it was along with the one in Stuttgart, the only fine arts schools in Germany open to young women

MH : And you, Robert, did you also enroll in that school?

RM : No. I had very different plans. I wanted to become an aeronautical engineer because I was passionate about technology, progress, and the new developments in aviation. Then, during a flight in 1916, while I was still a very young test pilot aboard a plane we used to call the “Gotha Pigeon”, my aircraft caught fire and crashed. Miraculously, I wasn’t too badly injured, and I was sent to recover in a military hospital. As fate would have it, that hospital had requisitioned part of the premises of the Weimar School of Art.

MH : Lucky you survived that crash.

RM : `Yes, but unfortunately, I was never able to pilot again afterwards. However, it was thanks to that accident that I discovered my interest in the arts and a little later, my love for Ella. Luckily, in Weimar, women were allowed to study the visual arts: modernity had arrived here even before the Bauhaus settled in!

MH : What do you mean?

EBM : The Bauhaus, which opened in 1919, is one of the reasons the city is so well-known. But before that, the Belgian architect Henry van de Velde played a major role in Weimar’s cultural life and had an undeniable influence on the later founding of the Bauhaus. He brought together many disciplines in his School of Applied Arts and encouraged multidisciplinary studies. He left behind a fertile ground for Walter Gropius. Unfortunately, due to his nationality, van de Velde had to leave Weimar at the outbreak of the First World War.

MH : And then the Bauhaus came to Weimar!

RM : First of all, that terrible war had come to an end, the monarchy had been abolished in Germany, and all of a sudden, Weimar found itself at the heart of the first German republic, which was proclaimed there on the eve of the armistice. We actually knew Friedrich Ebert quite well — he was a social-democratic trade unionist who then became the president of Germany. There was suddenly a lot of energy in the air, and everywhere people believed in progress. Walter Gropius had heard about Weimar, and especially about Henry van de Velde, when he was considering founding a school that would bring together the fine arts and applied arts. On his first visit to Weimar, he toured the city in an open carriage with his wife and the city mayor, and was shown, among other things, the places where artists had their studios so it didn’t take long before he came across our four studios on Schulstrasse.

MH : Why four studios?

EBM : Robert and I each had our studios on opposite sides of the street, separated by only three steps which gave Robert the idea to create the Weimarer Signet, the stamp we both used as our signature, often printed in red, which we adapted in different sizes and which can be seen on most of our works from that period. And besides Robert and myself, Johannes Molzahn and Karl Peter Röhl also had their studios on that street. Walter Gropius was so impressed by the quality of our work that he organized the inaugural Bauhaus exhibition, even before the school officially opened, with the four of us, to promote his new ideas. Because after the First World War, there was practically nothing left. Everything had to be started again and rebuilt.

MH : But you left Weimar very quickly after that, didn’t you?

EBM : Robert and I briefly studied at the Bauhaus. But we were already accomplished artists, and the Bauhaus felt too dogmatic to us, so we actually left Weimar quite quickly. But there was also another reason for our move. Robert and I got married in Weimar in 1919, and our first child (Hans) was about to be born. Robert inherited one of the seven pigment mills owned by his family, called the Schmelz, near Frankfurt. We still live today in that former mill in Vockenhausen, in the Taunus Mountains, and it’s hardly believable, but in the 1920s, part of the European avant-garde used to gather there. We’ll come back to that later.

MH : Let’s briefly return to Weimar—tell me about Johannes Molzahn.

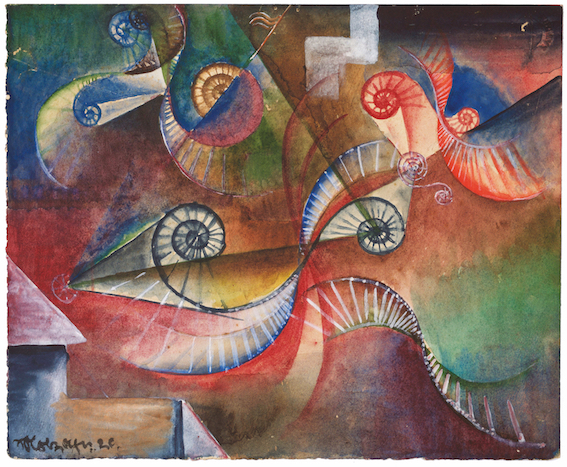

RM : Ah, Johannes. He was my best friend for a long time, and also a very good friend of Ella’s. He painted in a futurist spirit, inspired by the human figure and by geometric forms found in nature, using very bright color ranges that contrasted with the primary colors that were all the rage among the Constructivists at the time.

EBM : Johannes didn’t stay long in Weimar either. He moved away and went to teach in Magdeburg. In honor of our deep friendship, we gave our son Hans the name Johannes (Molzahn), since Johannes was his godfather. Johannes named his first son Michael, and Robert was his godfather. We used to visit each other often and stayed in touch through letters and postcards.

RM : Johannes also wanted to bring me to Magdeburg, to the university led by Bruno Taut, whom we admired, particularly for his futuristic Glass Pavilion presented in 1914 in Cologne as part of the Werkbund Exhibition. Unfortunately, it didn’t work out, and Johannes eventually moved to Breslau. Later, the Nazis drove him out of Germany, and he took refuge in America.

MH : And then you met Kurt Schwitters.

EBM : Kürtchen, “Little Kurt”…

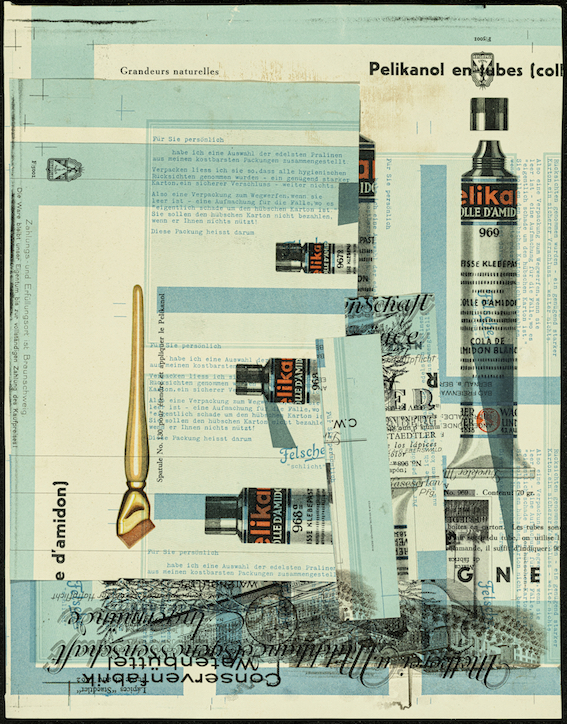

RM : Kurt was, along with Johannes, our closest friend during the 1920s. He often visited us at the Schmelz, and we would frequently visit him as well, along with his family and children, in Hanover. Closely linked from early on with Dada, his work was polymorphic, abstract and poetic, vocal, graphic, and brutalist. He created several thousand collages from fragments of salvaged paper, newspaper clippings, and advertising messages, which redefined the way art was approached at the time.

EBM : Kurt was one of my greatest admirers; he was deeply interested in my work. In my drawings and collages from the 1920s on the decomposition of light, he saw all the colours of the rainbow, including their intermediate tones. According to Kurt, one could have built an entire painting method on that basis. Following my suggestions, he said that the new painting should move beyond the opposition of the three primary colours and be re-evaluated through the transitions of the colours of the rainbow. He was absolutely convinced of it. I later dedicated a series of drawings to him, in honour of Anna Blume. He always recited Anna Blume and the Ursonate at our place, at the Schmelz.

RM : We pissed together in the snow, drawing swastikas in front of the village bar, which was frequented by the local Nazis. And in 1927, we took a road trip to Holland together. Kurt and I played dice to win the front seat next to Ella. During that trip, we visited, among others, Mondrian, Mart Stam, Oud, and Hannah Höch.

MH : Robert, Egidio Marzona once said in an interview [1] book that there was a fabulous envelope under your couch. Can you tell us more about it?

RM : Kurt didn’t just work on his poems at our place, he also made a lot of collages there, and left us about fifteen of them. I kept them all in one envelope. Today, we still have two. Whenever something needed fixing on the roof or when we were sick, we unfortunately had to part with one of those collages. Bills had to be paid, and as artists, we had no health insurance.

EBM : Kurt also took a few of our early works with him to the United States and convinced Kathrin S. Dreier to include us in her collection of concrete art. She had founded the Société Anonyme collection with Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp — it’s now held at Yale University — and organized traveling exhibitions throughout the United States. Kathrin S. Dreier did buy works from us, but we were only paid for them at least fifteen years later, after the war had ended! I was one of the very few women in that collection, and together with Kurt, Johannes, and Willi Baumeister, we were among some thirty German avant-garde artists represented and by far the most strongly represented nationality.

MH : That also explains why your work can be found today in many major museums and private collections in the United States?

EBM : Yes, it’s true that this collection and its traveling exhibitions made us known there, but Ilse also always helped us a lot in the United States.

MH : Ilse Bing, Mart Stam and you – a magical trio!

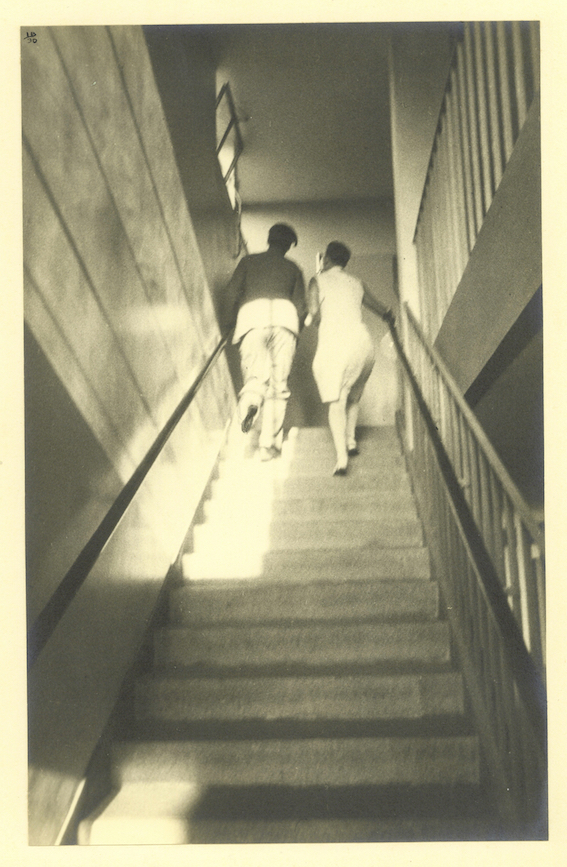

EBM : Yes, you could say that. Without Mart Stam, I might never have met Ilse Bing, who became a very close friend. Mart Stam knew that, in addition to photography, I had started filming. I was interested in light and shadow. Through photography and film, I was very close to Constructivism. Mart asked me if I could make a promotional film about the Budgeheim, a retirement home he had just built in Frankfurt with Werner Moser in 1929. And while I was filming at the Budgeheim, Ilse Bing took fantastic photos in that building. It was no coincidence that she was there. Mart had told her about me. The chemistry between us was immediate, and to this day, we have remained very close. We both saw life and abstraction as one. Sadly, Ilse, like Kurt Schwitters and almost all our other artist friends, had to flee the Nazis. She was lucky and managed to leave Marseille for New York on one of the last boats. After the Second World War, she sent us packages with supplies and food.

MH : And Willi Baumeister? What was he good at, besides making Spätzle?

RM (Laughs) : Willi and I had more in common than just our love of Spätzle [2]. He was a very good painter, who had thoroughly absorbed the principles of Purism and adapted them to the human figure, before turning to abstraction. Like me, he was also a talented commercial artist. He was part of the Ring Neuer Werbegestalter, which we had founded at our place, at the Schmelz. He was also a member of the Das Neue Frankfurt association, like Mart Stam; it was an initiative aiming to make Frankfurt a modern and social city. Baumeister came to Frankfurt and took over the direction of the Städel school. At the time, Ella and I had our studios in Frankfurt, and he was often a guest at our home, at the mill.

MH : And how did it all end?</span

EBM : Alongside our artist friends, like Schwitters, El Lissitzky, and Moholy-Nagy, the Russian filmmaker Dziga Vertov also visited us. The Schmelz was one of the crucibles of the European avant-garde before 1933. While I was working on my fifth film, The Last Election, I was arrested by the political police. My film material was confiscated and destroyed. I was filming political rallies for what would be the last free election in Germany before the Nazis came to power when I was arrested. Robert did everything he could to get me released as quickly as possible. Suddenly, we realized that nothing would ever be the same again. Dark times were coming.

RM : Our practice was labelled degenerate art. Degenerate art! What a horrible term. Anything that was different, anything that expressed progress, had to be wiped out.

EBM : Remaining in Germany, we had to be extremely discreet. Robert didn’t resume his work until the mid-1950s, and I continued drawing a little, in secret. Most of our friends left Germany. It’s hard to say what our lives would have been like without the Nazis.

[1] BRANICKA, Monika, RATHGEBER, Pirkko ; 100 Fragen an Egidio Marzona, Merve Verlag, 2024

[2] Spätzle: a pasta specialty traditionally homemade in southern Germany

[3] Ring Neuer Werbegestalter: The Circle of New Advertising Designers, is a collective of artists committed to promoting graphic design. It was founded in Schmelz in 1928 and contributed to exhibitions throughout Europe from 1928 to 1931

Editor’s notes:

Ella Bergmann-Michel, born in 1896 in Paderborn and died in 1971 in Vockenhausen at Schmelzmühle

Robert Michel, born in 1897 in Vockenhausen and died in 1983 in Titisee-Neustadt.

Johannes Molzahn, born in 1892 in Duisburg and died in 1965 in Munich.

Karl Peter Röhl, born in 1890 in Kiel and died in 1975 in Kiel

Kurt Schwitters, born in 1887 in Hanover and died in 1948 in Kendal, Cumbria, England.

Ilse Bing, born in 1899 in Frankfurt am Main and died in 1998 in New York.

Mart Stam, nborn in 1899 in Purmerend, Netherlands and died in 1986 in Goldach, Switzerland.

Willi Baumeister, born in 1889 in Stuttgart and died in 1955 in Stuttgart.

MORE INFORMATIONS:

// Press kit

// Ella Bergmann-Michel

// Robert Michel

// Together we were building a new world. Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel and their avant-garde circle (07/06-08/08/2025 | Paris)

Category:

Exhibitions

Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel et leur cercle d’avant-garde – Galerie Éric Mouchet, Paris (C) Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025-2

Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel et leur cercle d’avant-garde – Galerie Éric Mouchet, Paris (C) Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025-3

Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel et leur cercle d’avant-garde – Galerie Éric Mouchet, Paris (C) Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025-4

Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel et leur cercle d’avant-garde – Galerie Éric Mouchet, Paris (C) Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025-5

Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel et leur cercle d’avant-garde – Galerie Éric Mouchet, Paris (C) Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025-6

Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel et leur cercle d’avant-garde – Galerie Éric Mouchet, Paris (C) Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025-7

Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel et leur cercle d’avant-garde – Galerie Éric Mouchet, Paris (C) Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025-8

Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel et leur cercle d’avant-garde – Galerie Éric Mouchet, Paris (C) Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025-9

Ella Bergmann-Michel, Robert Michel et leur cercle d’avant-garde – Galerie Éric Mouchet, Paris (C) Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025

Ella Bergmann-Michel, Ohne Titel – (Untitled), 1920. India ink and pencil on paper, 32 x 27,5 cm © Bertrand Michau

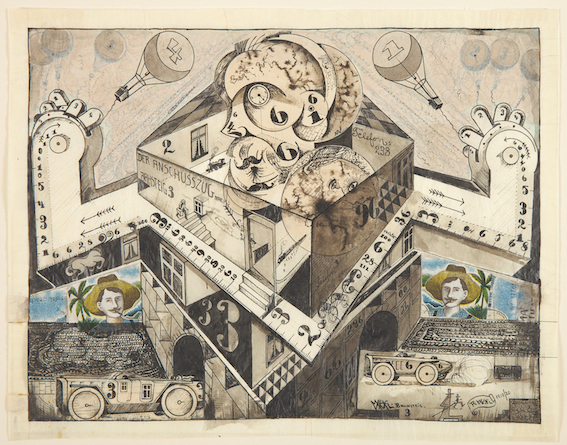

Robert Michel, BAHNSTEIG 3 (Quai de gare), 1920. Collage and ink on paper, 25 x 32,8 cm © Bertrand Michau

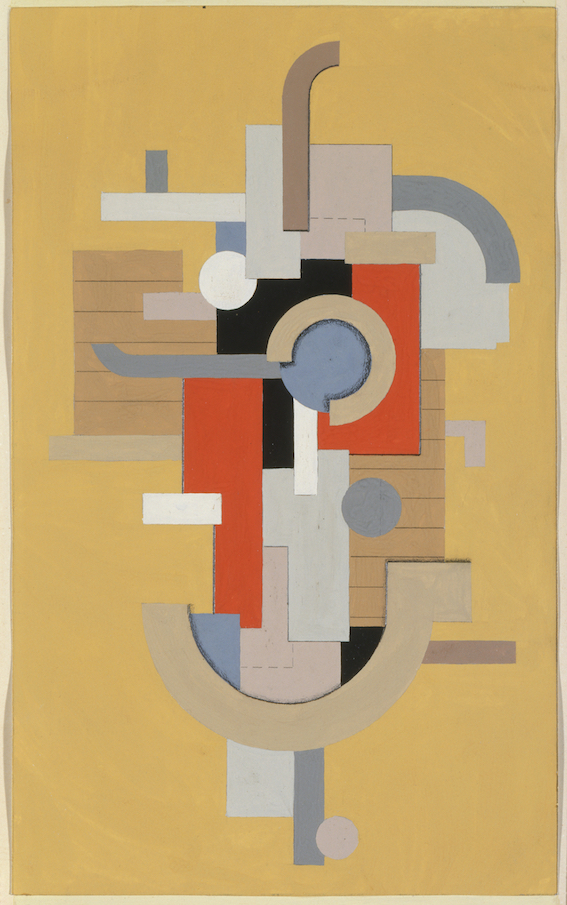

Willi Baumeister, Ohne Titel (Maschinen-Komposition), 1921. Collage on cardboard, pencil and gouache, 43,5 x 30 cm

Reproduktion

Johannes Molzahn, Ohne Titel (untitled), 1921. Gouache on Japanese paper, 21,7 x 26,6 cm © Bertrand Michau

Karl-Peter Röhl, Abstrakte Komposition (Abstract composition), 1919. Oil on canvas, 97 x 66 cm

Ilse Bing, Mart Stam and Ella, Budgeheim, 1930. Silver print, 28 x 17,8 cm