IL ÉTAIT UNE FOIS ENTHÉORIE

And they lived happily ever after… And so did they (Et ils vécurent… Et iels vécurent !)

By Matthieu Lelièvre

What remains of the fairy tale when it ceases to reassure? When its heroes falter, when its princesses feel too constrained by a predetermined fate, and when morality dissolves into the shadow of desire? Drawing us into a floating realm between childhood and disenchantment—where marvelous tales become the fractured mirrors of identities in search of truth—Enthéorie, Jérémie Danon’s latest short film, offers a singular interpretation of the fairy tale while at the same time renewing its codes. He does not merely use the genre as a narrative framework; he deconstructs it even as he probes its critical possibilities. The fairy tale, traditionally meant to channel fantasies, becomes here the very site where forms of existence express themselves—forms that social norms strive to stifle, unable to assimilate them. These are not impulses to be mastered, but identities searching for form, subjectivities in motion, refusing to be assigned to a category.

At first glance, Enthéorie seems to replay the archetypes of medieval romance: one can recognize the influence of Yvain, the Knight of the Lion by Chrétien de Troyes, a 12th-century chivalric tale inspired by Celtic tradition. That story recounts the quest of a disgraced knight who, in order to regain his wife’s love, must endure a series of ordeals and battles until he confronts his own madness. Jérémie Danon multiplies such references: the visual universe, the offbeat dialogues, and the absurd situations summon echoes of Don Quixote, Jean Cocteau, and Jacques Demy alike. Each viewer is invited to project their own imagination onto this palimpsest of references. Yet the film soon shifts: the fairy tale is no longer the story of an external accomplishment, but of an inner journey. Danon seeks to free the narrative from the normative trappings that confine it—virile hero, passive princess, conservative moral order—in order to bring forth a tale of self-knowledge. Here, it is not the other who stands in the way of happiness, but the self, in its often conflicted relationship with desire, aspirations, and conditioning. This is not an individualist logic, but a call to listen sincerely to oneself, in relation to the world—a relation that may or may not include others.

As a literary genre and oral tradition, the fairy tale is commonly considered to be addressed to the child. Its function is to channel fantasies and to accompany the development of the imagination. Bruno Bettelheim, in The Uses of Enchantment (1976), emphasized how the structures of the fairy tale operate in ways similar to the child’s psyche: they allow the child to project anxieties and to overcome them symbolically. These stories, often beginning in a realistic setting (such as Little Red Riding Hood going to visit her grandmother), quickly shift into a symbolic realm where the child can experiment safely with the fundamental conflicts of development. Yet this reading, largely grounded in a Freudian framework, has not escaped criticism. Didier Eribon, in Escaping Psychoanalysis (2005), underscored the limits of such approaches, pointing out that a psychoanalytic framework, by naturalizing certain social norms, becomes an obstacle to a more radical renewal of queer theory. It freezes identities, interprets deviations from the norm as symptoms, and thereby prevents us from thinking the plurality of ways of being oneself.

The fairy tale form, as we have said, is associated with childhood—this encrypted narrative one grasps intuitively, through successive thresholds often crossed in solitude. Yet Enthéorie rejects the conventional resolution, “ils vécurent heureux et eurent beaucoup d’enfants” (“they lived happily and had many children”). This stereotypical ending itself comes under scrutiny. The English version—“they lived happily ever after”—suggests eternal happiness; the French version, more conditional—“ils vécurent heureux”—seems to tie happiness to procreation. Jérémie Danon thus raises the question: must fulfillment necessarily rest on such stakes as couplehood or parenthood? Is this closing refrain anything more than a narrative lock, imposed to ensure that an ending exists at all?

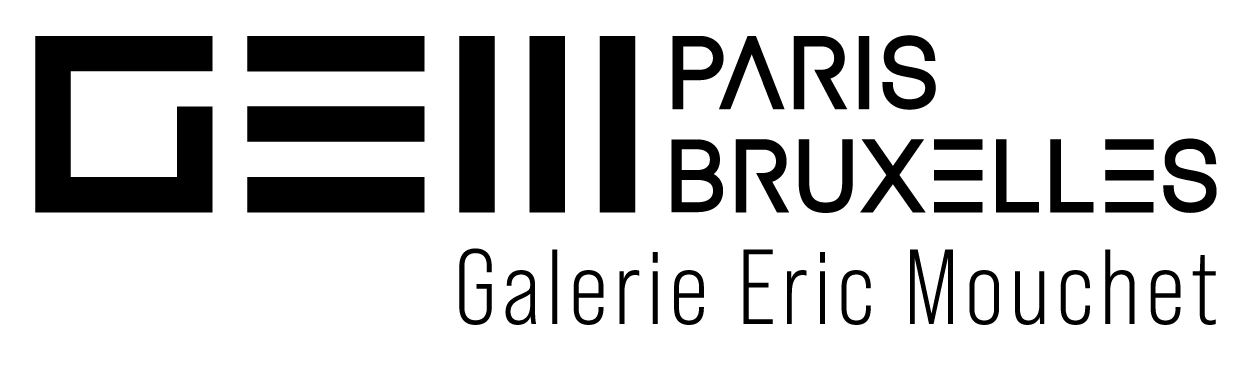

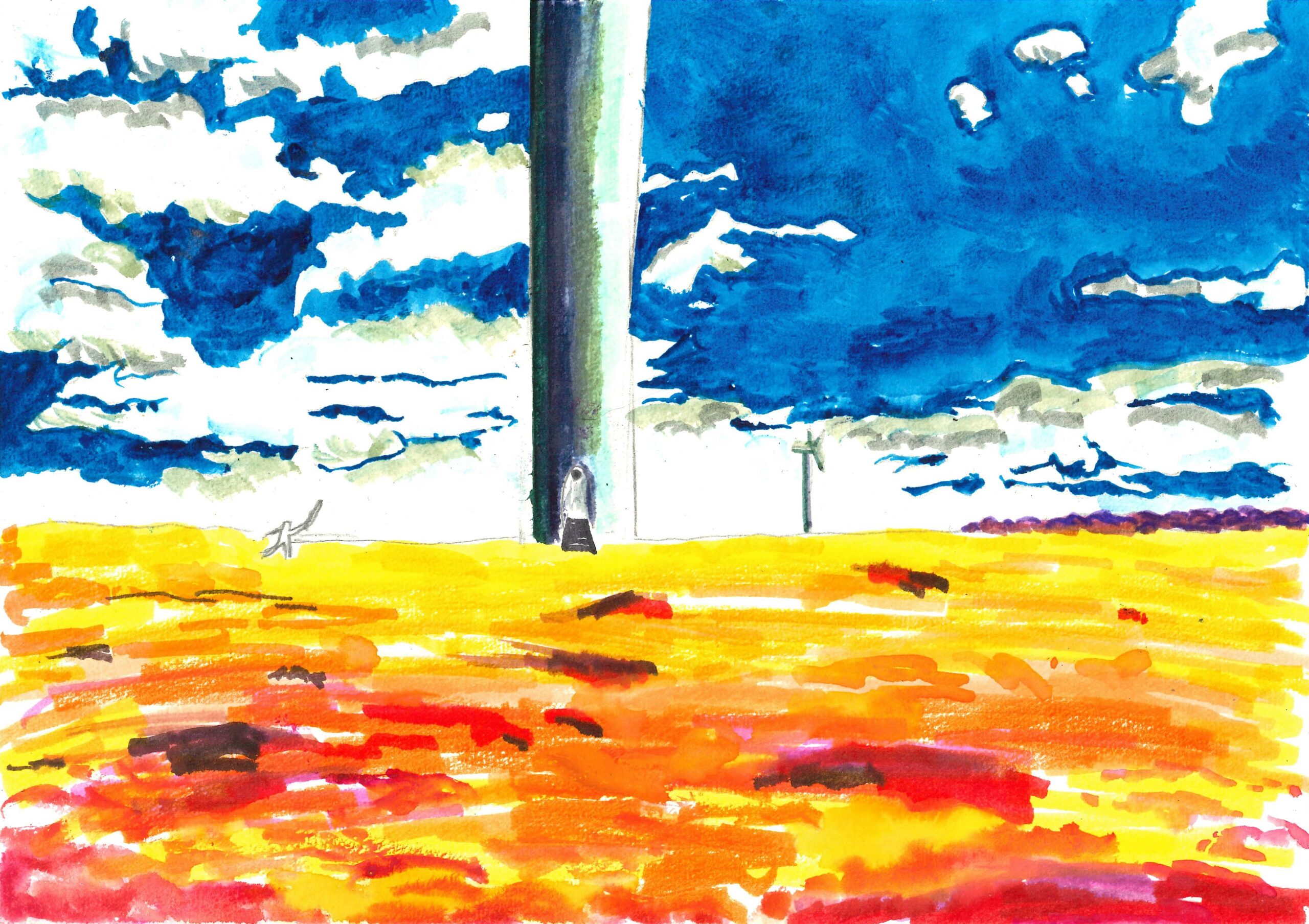

Enthéorie carries us into a world that might follow a familiar thread, were it not for the characters’ inner unease—the dissonance between the roles assigned to them and their personal aspirations. It is from this intolerable gap that the quest emerges. Danon populates his tale with alternative figures: princesses who refuse the imposed ending, who find fulfillment in an adventurous, solitary life; princes who become princesses; indeterminate figures who reject any assignation. Here, the traditional hero gives way to an anti-hero—or rather a wandering, in-between, unclassifiable figure, more human than glorious. This figure, of which Don Quixote is the archetype, is neither all-powerful nor absolute, but porous, fragile, caught in its own contradictions. The unnamed knight here does not move toward an ideal but seeks to understand why he walks at all: this tale, where wind turbines replace windmills, no longer recounts victory over the world, but the desire for lucidity.

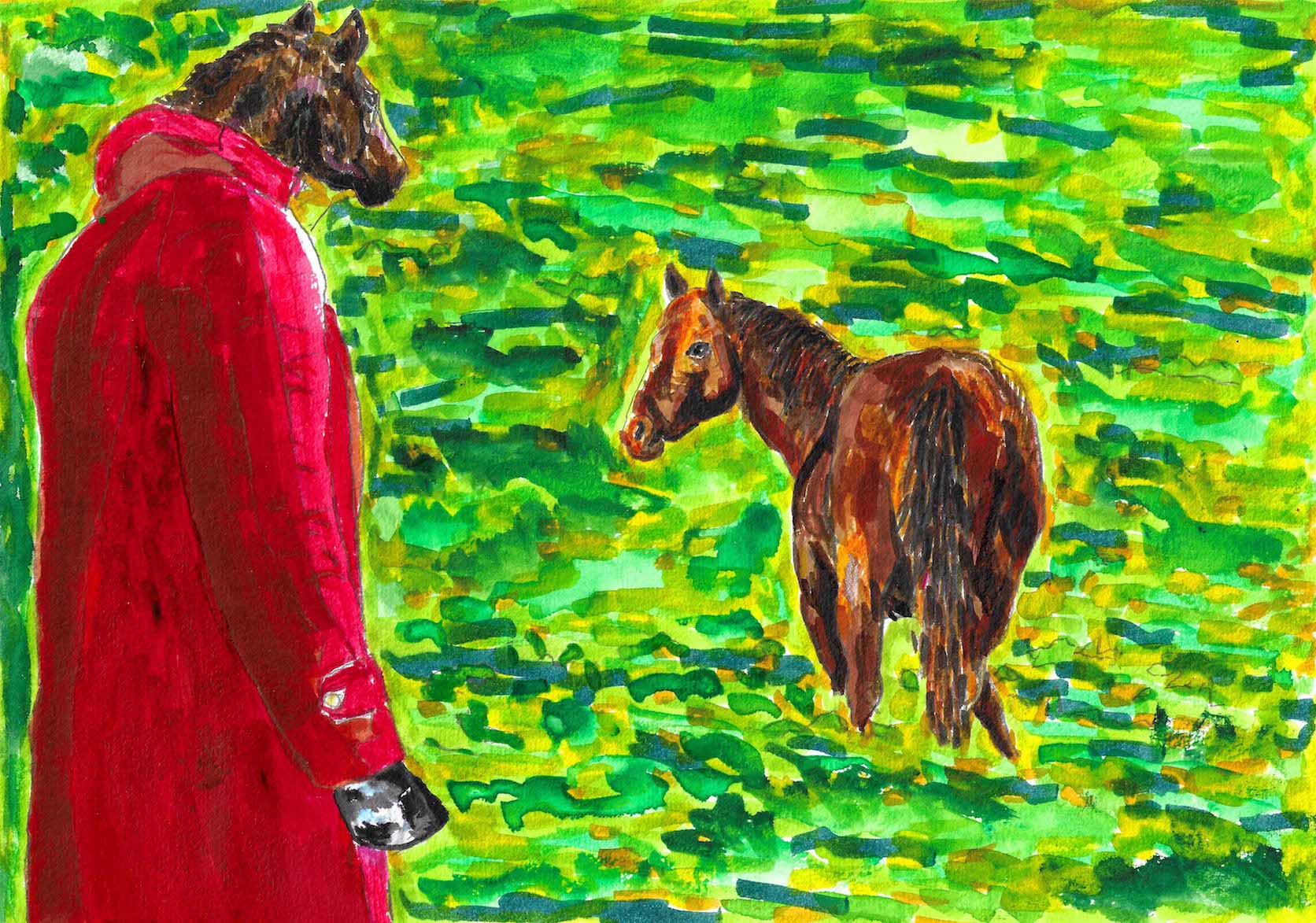

In Enthéorie, knights wait their turn without really knowing why. This existential suspension, this absurd waiting, outlines the true subject of the film: determinism. Whether moral, social, or historical, it rests on conditioning that is often invisible. The most painful truth is that the allies of this conditioning are sometimes precisely those who love us most, who fear seeing us wander, deviate, or take another path. The fairy tale, then, becomes a space of resistance against this injunction to succeed, to fulfill a destiny that would necessarily conclude with a “happily ever after.” It is no coincidence that the figure of the fool, omnipresent in literature, theater, and painting, takes center stage in the land of Enthéorie. The fool is the one who escapes numbers, queues, and quests. He does not seek to meet the princess. His madness—or is it his freedom?—places him outside roles, outside functions. It is precisely this exit from the social game that grants him liberty.

Through its characters and narratives, Enthéorie might at first seem to address themes such as gender assignment, social roles, or neurodivergence. Yet what Jérémie Danon proposes is perhaps even more fundamental: through this film, he offers a meditation on forms of existence that resist dominant narratives and injunctions. If the fairy tale has survived across eras, if it has been reclaimed by psychoanalysis, it may be because it remains an open matrix, capable of interpreting desires and fears—both in children and in adults. The poetic force of Jérémie Danon restores to this form its original power: the power to bring forth profound existential questions through images, symbols, and detours. It is within this tension between collective narrative and the intimacy of each viewer that Enthéorie finds its strength.

MORE INFORMATIONS:

// Jérémie Danon

// Press kit

// Il était une fois Enthéorie (08/11/25-10/01/2026 | Paris)

Category:

Exhibitions

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_1

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_2

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_3

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_4

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_5

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_7

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_8

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_6

Jérémie Danon, Le Prince Crapaud, 2025

Jérémie Danon, Alfred, 2025

Jérémie Danon, Le roi bleu, 2025_

Untitled (Storyboard), 2024_56

Untitled (Storyboard), 2024_57

Untitled (Storyboard), 2024_41

Untitled (Storyboard), 2024_18

Untitled (Storyboard), 2024_4

Untitled (Storyboard), 2024_54

Untitled (Storyboard), 2024_60

Untitled (Storyboard), 2024_13

Untitled (Storyboard), 2024_51

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_10

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_11

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_13

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_15

Jérémie Danon, vue d’exposition Il était une fois Enthéorie, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2025 © Hafid Lhachmi – ADAGP Paris, 2025_20