Berliner Pop Und Politik! – Ulrich Baehr & Peter Sorge

The Pop-Art wave, ushered in in the 1950s in the UK by Richard Hamilton (1922-2011) and Eduardo Paolozzi (1924-2005), heralded the renaissance of figurativism and of a new optimism against a backdrop of the consumer society. Having won acclaim in the US thanks to Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997), Andy Warhol (1928-1987) and Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008), awarded the Gran Premi at the Venice Biennale in 1964, it swept across Europe and arrived in West Germany in the early 1960s just after the Berlin Wall went up.

The sudden burgeoning of the German Pop scene from 1963 was spread across the different regional capitals and their art schools, mainly Munich, Frankfurt, Düsseldorf and Berlin. These last two cities witnessed the flourishing careers of the most important representatives of this generation of artists: Gerhardt Richter (born in 1932), Wolf Vostell (1932-1998) and Sigmar Polke (1941-2010), all of whom studied at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. The Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Berlin was another notable creative center. It was here that Karl Horst Hödicke (born 1938), Ulrich Baehr and Peter Sorge (from 1958 and until 1965 and 1964, respectively) received their training. Most of these artists studied under painters twenty years their elder, most of them proponents of “informal art”, an abstraction that the younger generation of artists was to replace with a new figurativism that for some testified to a new way of life inspired by America and made of abundance, advertising and marked optimism, and that for others represented the memory of a war they had lived through as children and the Cold War they experienced every day.

Some of these artists discovered the Pop movement in Germany’s Amerikahäuser (Houses of America), American cultural centres established in around fifty cities after the Second World War and dedicated to the “re-education” and “democratization” of German society according to American standards. Others got to know it abroad. Ulrich Baehr says that it was during a year of study at the École des Beaux Art in Paris in 1963 that he discovered the works of young American artists, notably Roy Lichtenstein, at the Ileana Sonnabend gallery only a few hundred meters from the School.

The German Pop movement with its mosaic of very different personalities also took off outside the schools. Creative centres, often self-managed, emerged in university towns across the country. In Düsseldorf, Richter, Lueg, Polke and Kuttner opened the “First exhibition of German Pop art” in May 1963 in a former butcher’s shop, and in October of the same year, Richter and Lueg gave a now legendary performance in a former furniture store entitled “Leben mit Pop: eine Demonstration für den kapitalistischen Realismus” (“Living with Pop: a Demonstration for capitalist Realism”), whose title obviously echoes Socialist Realism, the artistic doctrine that held sway on the other side of the Iron Curtain. In Berlin, Baehr and Sorge co-founded a gallery called Grossgörschen 35 in June 1964 alongside fourteen other painters including Hödicke and Markus Lüpertz (born in 1941). The gallery’s mission was to replace Tachism and Art Informel with figurativism. Eva and Lothar C. Poll joined the group in 1966, and created a gallery which has since represented many of the artists from Grossgörschen 35, particularly Ulrich Baehr and Peter Sorge, but also their respective spouses, Bettina von Arnim (born in 1940). and Maina-Miriam Munsky (1943-1999). While the 1960s are generally seen as the era of women’s emancipation, paradoxically, women artists are few and far between and invisible within the Pop movement.

There was a great deal of contact between Düsseldorf and Berlin owing to the higher degree of political engagement among artists from those two cities than for example those from Frankfurt or Munich. Vostell left Düsseldorf for Berlin in 1970.

Ulrich Baehr and Peter Sorge, living and studying in a Berlin divided by the Wall since 1961, were both highly attuned to the Cold War atmosphere omnipresent in a community surrounded by the communist world and dependent on the West for its survival. Each in his own way focuses his artistic work on expressing the threat of war hanging over them.

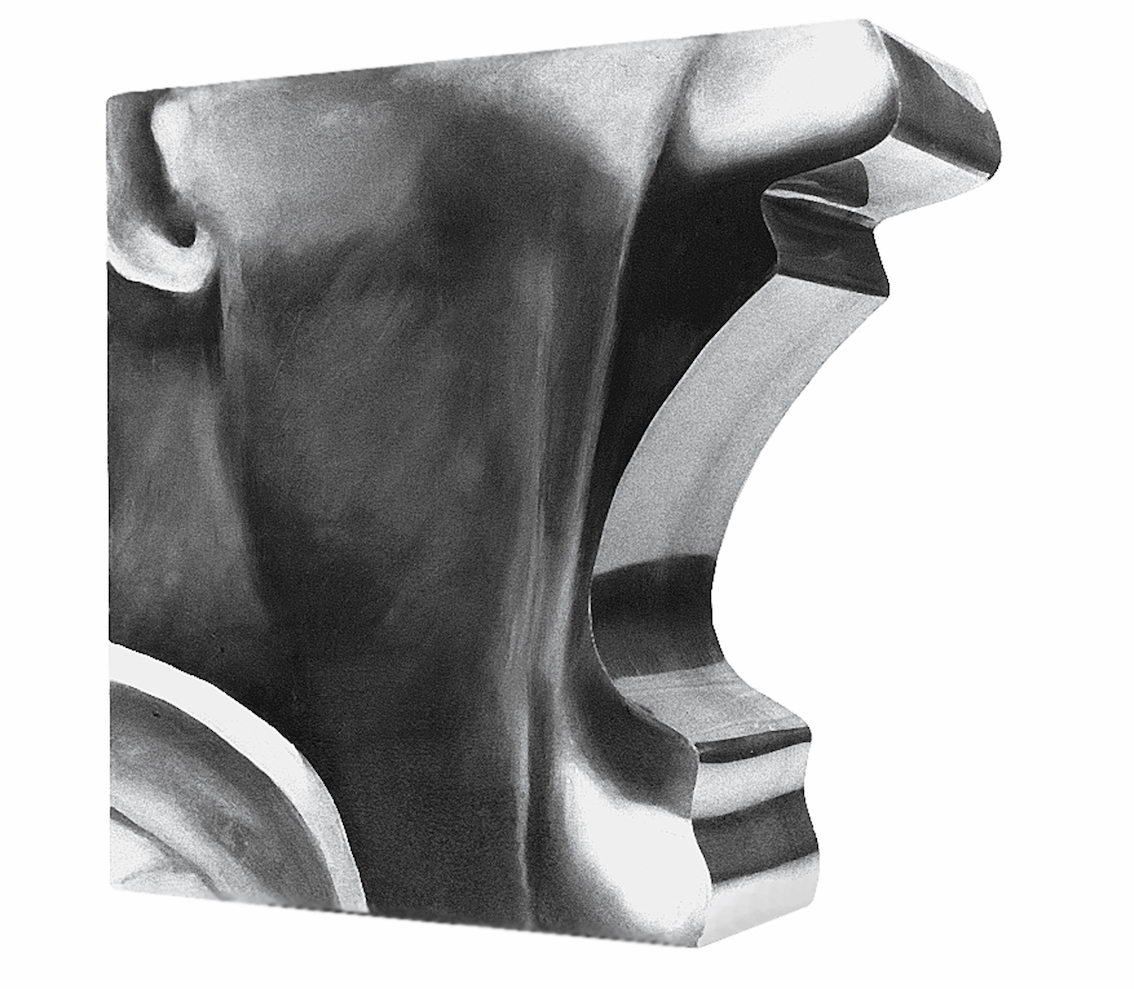

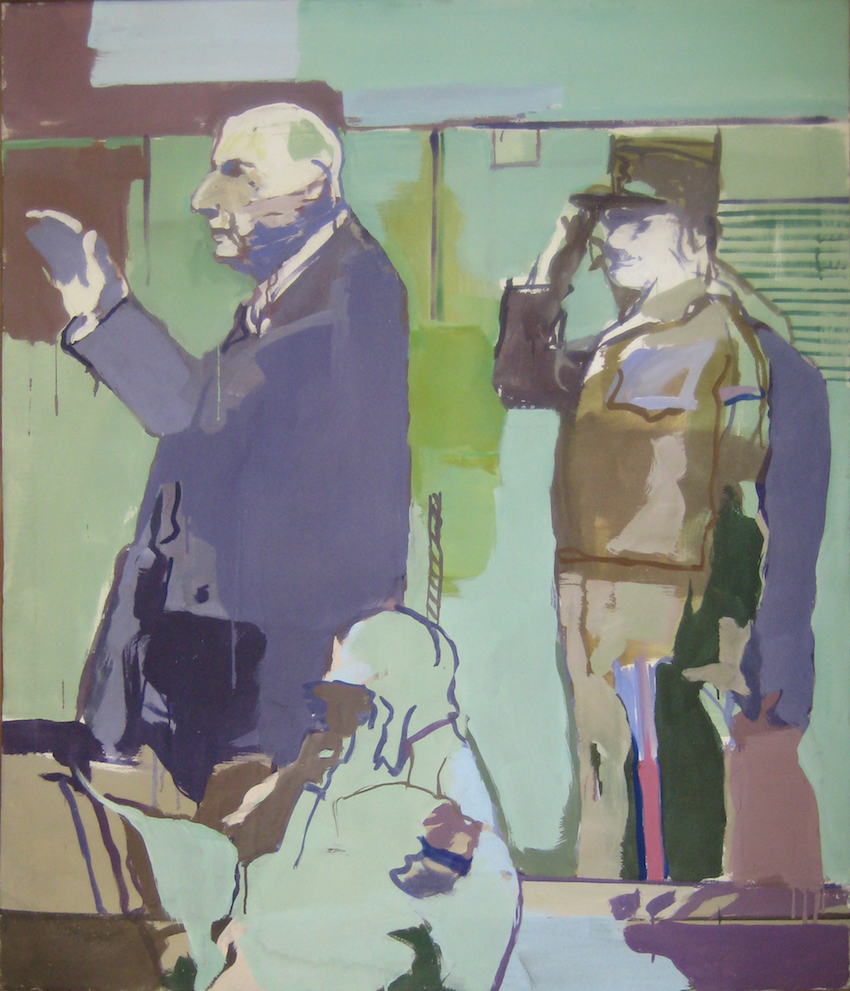

Ulrich Baehr (born in 1938), working from his studio above Checkpoint Charlie, the main crossing point between East and West Berlin, painted in the 1960s the major events of recent history, taking his inspiration from famous press photographs. His images, including the portrait of Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin at the Yalta conference, are obviously immediately identifiable. Reworking them with large brush strokes and bright colours and sometimes leaving them unfinished lends the paintings a cathartic dimension, compromised somewhat when the portrait of Hitler features. To show how the figure of Hitler was hyper-publicized, in 1970-72 Baehr produced painting-sculptures of details from the photographic portraits of the dictator, which although fragmentary are immediately recognisable, giving food for thought on the immense capacity of the human brain to fill in gaps. These painting-sculptures are now almost all kept in German museums, including the Sprengel Museum in Hanover, the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn, and the Berlinische Galerie in Berlin. In the years that followed and up to the present day, Baehr continued his career as an excellent colourist painter, a witness to key world events. He created a whole series of landscapes of a Berlin bristling with cranes even as following the fall of the Wall, his Checkpoint Charlie district was thoroughly revamped. Even his more recent landscapes testify to the melancholy caused by the threat that hovered over his city for so long.

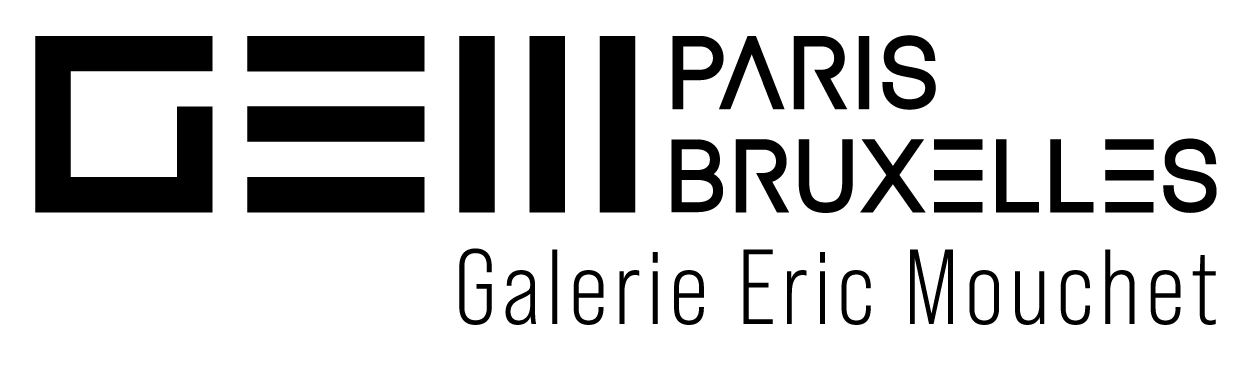

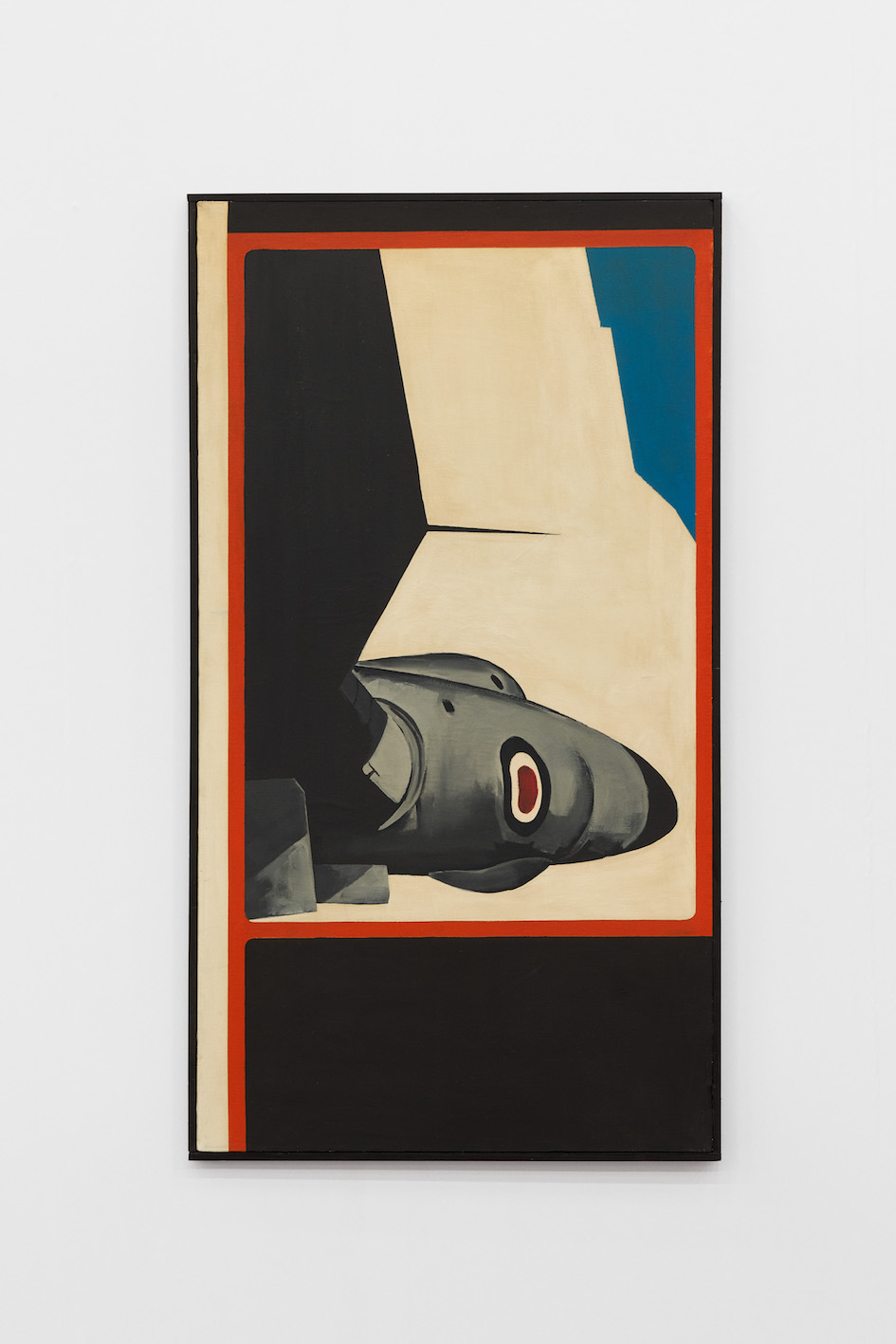

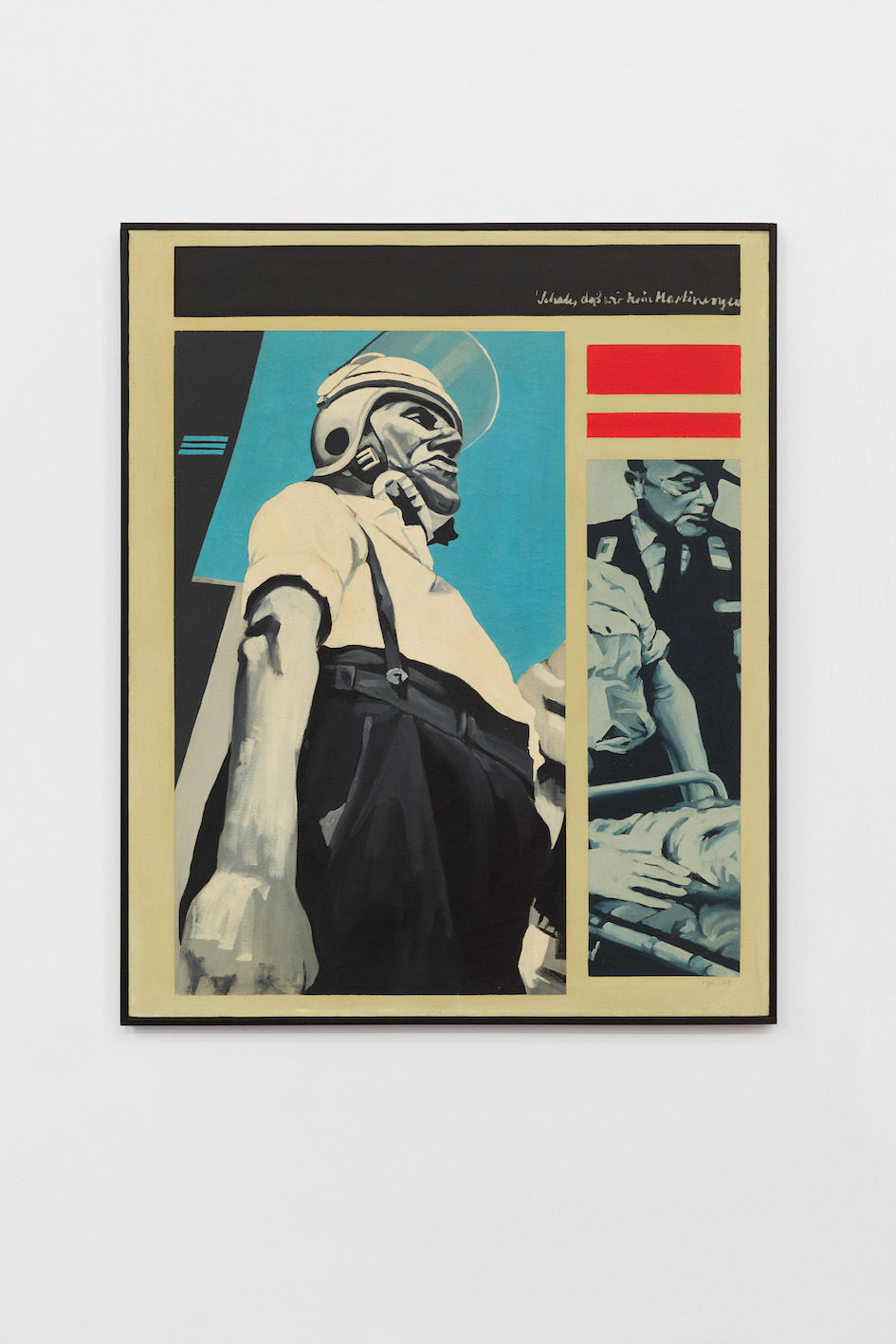

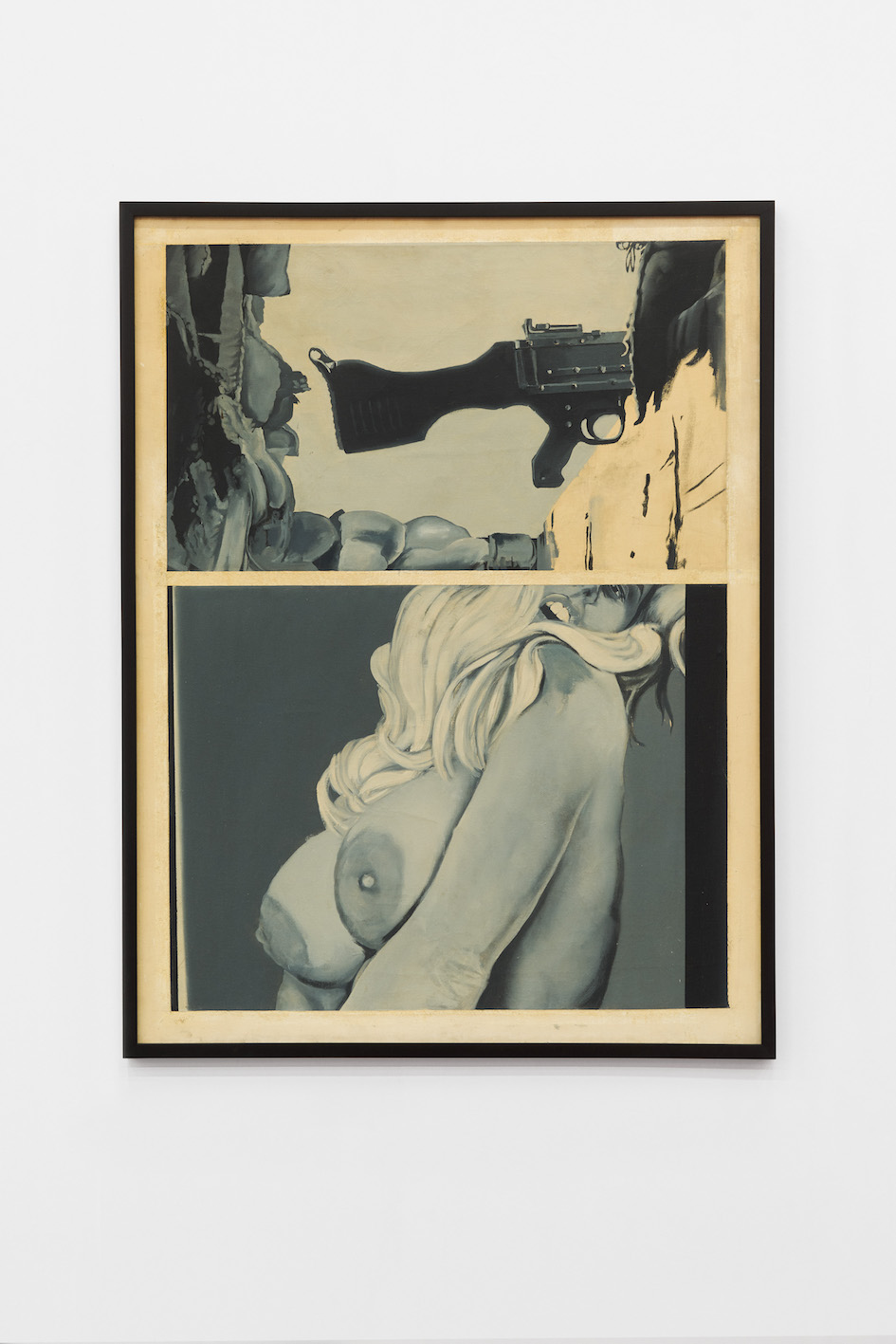

Peter Sorge (1937-2000), also a painter, designer, collage artist and engraver, used press clippings and magazine photographs for his collages and as inspiration for his paintings. Associated with a trend of Pop-politics known as “Kritischer Realismus” (“Critical Realism”), which also included the contemporary works of Erró (born in 1932), his work coldly juxtaposes images within the same work depicting violence, sexuality, weapons and bodybuilding in a way that makes him part voyeur, part aesthete. All his subjects seem chiseled with a scalpel. His paintings are composed of different fields separated by frames painted on the canvas or made using adhesive canvas tape. The subjects are framed as if we are watching them on television, in the cinema or through a film strip. Unlike Baehr, Sorge uses a colour range limited to blue, orange-red, white, and black, highly effective and typical of the magazine graphics of the time. From the 1980s onwards he hardly painted anymore, producing instead large drawings in which his virtuosity and the rage that his time evoked in him could be expressed. His colour range widened and his subjects, as violent as ever, extended to the environment, post-colonial clashes in Africa, and the wars in the former Yugoslavia. Their composition became more fluid. His works were still composed of fields but now these overlapped and interpenetrated each other, inevitably evoking the contemporary world of Rauschenberg where masterful drawing replaced photography.

Eric Mouchet

MORE INFORMATIONS:

// Press Kit

// Biography Ulrich Baher

// Biography Peter Sorge

// Berliner Pop Und Politik! (03/02-16/03/2024 | Paris)

Category:

Exhibitions

Ulrich Baher & Peter Sorge, exhibition view Berliner Pop Und Politik!, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2024. Photo Marie Lukasiewicz

Ulrich Baher & Peter Sorge, exhibition view Berliner Pop Und Politik!, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2024. Photo Marie Lukasiewicz

Ulrich Baher & Peter Sorge, exhibition view Berliner Pop Und Politik!, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2024. Photo Marie Lukasiewicz

Ulrich Baher & Peter Sorge, exhibition view Berliner Pop Und Politik!, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2024. Photo Marie Lukasiewicz

Ulrich Baher & Peter Sorge, exhibition view Berliner Pop Und Politik!, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2024. Photo Marie Lukasiewicz

Ulrich Baher & Peter Sorge, exhibition view Berliner Pop Und Politik!, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2024. Photo Marie Lukasiewicz

Ulrich Baher & Peter Sorge, exhibition view Berliner Pop Und Politik!, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2024. Photo Marie Lukasiewicz

Ulrich Baher & Peter Sorge, exhibition view Berliner Pop Und Politik!, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2024. Photo Marie Lukasiewicz

Peter Sorge, Bomber, 1969. Copyright Choreo

Peter Sorge, Knüppel, 1968. Copyright Choreo

Peter Sorge, Ordner I 1969. Copyright Choreo

Peter Sorge, Schwarzer Längsbinder, 1966. copyright Choreo

Peter Sorge, Untitiled (Leda), 1972. Copyright Choreo

Peter Sorge, Untitled (c. 1972). Copyright Choreo

Ulrich Baehr, Der gute Vater Hindenburg, 1966 (110 x 146 cm)

Ulrich Baehr, Deutscher Torso VI, 1972

Ulrich Baehr, Deutschland erwache, 1965 (120 x 145 cm)

Ulrich Baehr, Fries für Liebhaber, 1965 (120 x 217 cm). Copyright Friedhelm Hoffmann

Ulrich Baehr, Hindenburg und Ebert, 1965 (131 x 162 cm)

Ulrich Baehr, Le General, 1966 (142 x 122 cm)

Ulrich Baehr, Shakehands im Grünen, 1966 (136 x 185 cm)

Ulrich Baehr, Sportpalast, 1966 (128 x 108 cm)

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA