La R•Évolution française – Tony Regazzoni

Constantly foretold but never coming to pass is the twilight of the god Progress, the deity of promethean dreams, of mastery over time and space, and of overcoming the restrictions of space and time, incarnate in mundane items such as the car or the telephone. Rooted in aspirations for limitless speed and communications, these artefacts are now weighed down by the human and environmental disasters their production, infrastructure and emissions have engendered. Deactivating them while preserving their symbolic significance: this is the treatment to which Tony Regazzoni subjects them.

The background is France in the period 1970-1990: three decades that witnessed two oil crises, the first warning signs of ecosystem collapse, and the ascendancy of neoliberal policies; enough to turn the dream into a nightmare. This notwithstanding, for some at the time the “innovation” driven progress race was a no-holds-barred pursuit. In France, it took the form of public investment in telecoms R&D, the building of a network of highways, and public spending on culture for the benefit of the population at large, as well as technological advances by the major automotive manufacturers. In that sense it was still a time when the public authority had not yet fully yielded to unrestrained competition.

What of the relics of that past?

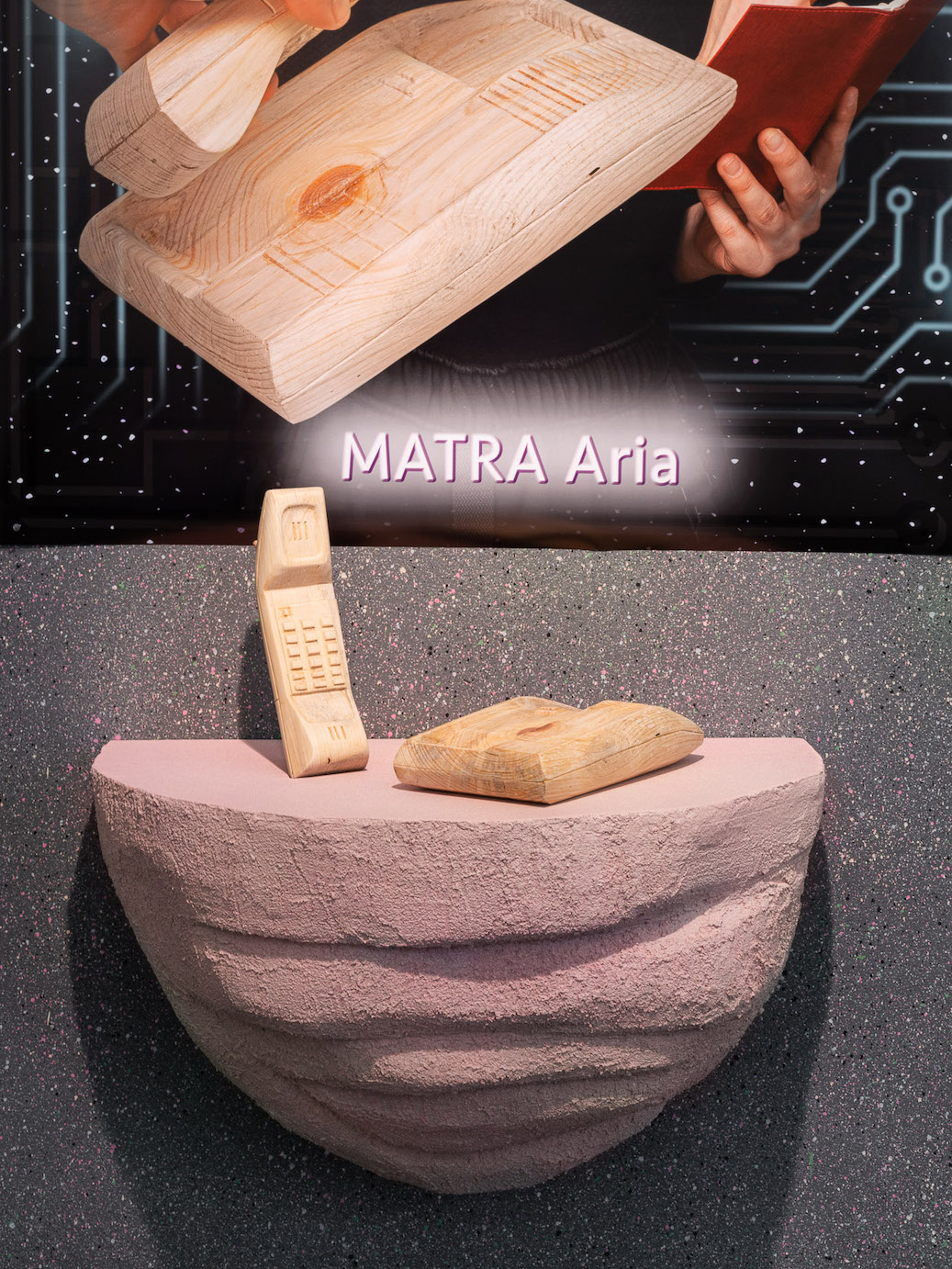

Consecrating them as idols of a former era is the vocation of the Musée des Anciennes Nouvelles Technologies (MANT – museum of former new technologies), which is devoted to the iconic artefacts of progress in telecoms. From its beginnings in 2018 the project develops a new iteration here with a series of long forgotten “made in France”[1] inventions reproduced in wood in 1:1 scale and accompanied by stands and pedestals reminiscent of the museum environment. Behind each of the sculptures a poster reproduces the advertising codes of the period, replacing the yuppies of the 1980-1990s with people combatting the kinds of symbolic, social and economic structures whose legitimacy derives only from promethean dreams. In other words, if a revolution is to take place, its vector is more likely to be political commitments than technological progress, which is revolutionary solely in its ability to maintain the established order revolving around its established orbit, i.e. to perpetuate it.

Rendered totemic through their representation using artisanal techniques, the relics also gain in prestige. Or at least that’s the impression conveyed in the first exhibition room. All along a mural inspired by a motif symbolising movement and speed, pyrographic engravings accompanied by everyday objects (a clock, a thermometer, an ashtray, a coat-hanger) depict Citroën, Renault and Peugeot cars against a backdrop of the public sculptures that adorn France’s highways. In other words, bathed in their aura of emancipation and freedom, the cars are reduced here to a utility and decorative level associated with the creative hobby of pyrography, a kind of “art for all” in the same way as the “highway art” judged to be “in poor taste” by bourgeois culture.

And by way of farewell to the former deity Progress: a car-telephone synthetic hybrid[2] embroidered on a nightclub bouncer-style bomber jacket against a backdrop of a setting sun.

Sarah Ihler-Meyer

(1) The Minitel and France Télécom’s “Bip Bop” mobile phone.

(2) The logo of Radiocom 2000, France’s first mobile telephony network, launched in 1986.

With the support of the galleries / exhibition of the Centre national des arts plastiques

MORE INFORMATION:

// Press Kit

// Tony Regazzoni

// La R•Évolution française (05/02-19/03/2022)

Category:

Exhibitions

Tony Regazzoni, vue d’exposition La R·Évolution française, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2022. Photo : Cyrille Robin

Tony Regazzoni, vue d’exposition La R·Évolution française, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2022. Photo : Cyrille Robin

Tony Regazzoni, vue d’exposition La R·Évolution française, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2022. Photo : Cyrille Robin

Tony Regazzoni, vue d’exposition La R·Évolution française, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2022. Photo : Cyrille Robin

Tony Regazzoni, vue d’exposition La R·Évolution française, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2022. Photo : Cyrille Robin

Tony Regazzoni, vue d’exposition La R·Évolution française, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2022. Photo : Cyrille Robin

Tony Regazzoni, vue d’exposition La R·Évolution française, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2022. Photo : Cyrille Robin

Tony Regazzoni, vue d’exposition La R·Évolution française, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2022. Photo : Cyrille Robin

Tony Regazzoni, vue d’exposition La R·Évolution française, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2022. Photo : Cyrille Robin

Tony Regazzoni, vue d’exposition La R·Évolution française, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2022. Photo : Cyrille Robin