FONDATION – Louis-Cyprien Rials

Between Paris and Brussels

30 May 2023

“To bring order to bookshelves is to exercise in a silent and modest manner the art of the critic”

The Proximity of the Sea,

Jorge Luis Borges

Fondation

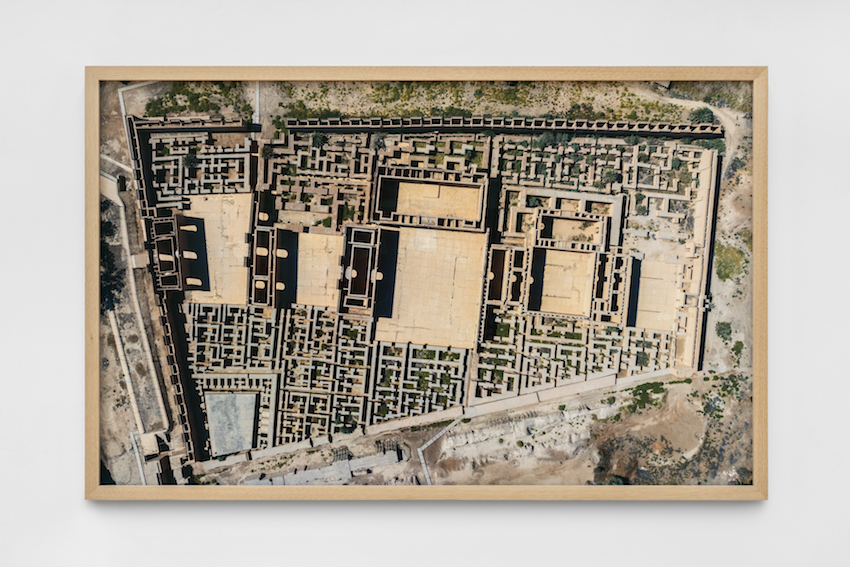

In a mirror image of his exhibition in Paris, Louis-Cyprien Rials presents his Fondation exhibition at Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels with a new film shot in Iraq plus an original work that is the fruit of his extensive documentary research. Each of the works shown in Fondation is in its own way an extension of the message conveyed by the artist in the Paris exhibition.

It all began with the work that lent its title to the exhibition: Fondation. Two slide carousels flick through 160 restored slides shot by the US army during the war in Iraq between 2003 and 2011. They offer a behind the scenes look at the military operation by exploring the sometimes-absurd everyday life of the military while affording spectators views of the country’s great tourism sites and iconic monuments. This catalogue and display endeavour points to what lies at the foundation of the artist’s perspective, which is to render back unto Iraq its foundational role as a country that was instrumental in building our world, twice over, in fact, as the artist sees it.

The land known as Iraq gave birth to our civilisation and to the first known form of writing, Mesopotamian cuneiform, developed more than 5000 years ago. It also sprouted many distinct ancient societies, among which Sumer, Akkad, Babylon and Assyria, which played a crucial role in the development of agriculture, commerce, architecture and elements of the legal system we still use today. They also founded the first known city-states.

Today, Iraq once again serves as a prototype of the world we live in. War has been with us for the past forty years with the same major protagonist – the US – either directly involved or sometimes wisely taking a back seat but still involved via its incredible military-industrial complex. In fact, war lies at the heart of what constitutes our globalised world. It is a war that seeks to impose a concept hammered home like a mantra by political and economic leaders alike, speaking as though they were the new masters of the universe: the creation of a ‘New World Order’ that tramples on international law to impose its own rules, starting with the weakest states and then moving on to its own citizens, to the detriment of the common good.

Similarly to Jean Bottéro, who in his foundational text Ancestor of the West: Writing, Reasoning, and Religion in Mesopotamia recontextualises the ancient Mesopotamians as the inventors of writing, and through it, the instigators of a new perspective on the universe and a new way of conceiving of, analysing and governing the world, Louis-Cyprien Rials recontextualises the foundations of the war in Iraq and tells us that the history of our globalised world is being written by a ‘narrator’ who is indifferent to the destruction of the cradle of civilisation and who toys with the peoples of the world.

The film Babel presented in Fondation explores this theme and offers a perspective on vestiges of the past and how they are used today in political, religious, and cultural propaganda. The video is directly inspired by the passage in the Old Testament in which the peoples of the world defied God by trying to build a tower that would touch the sky, whereupon God punished them by making them speak different languages so that they could no longer understand each other. Here, Louis-Cyprien Rials films the remnants of the ziggurat of Borsippa [1] just outside Babylon. The camera circles the ruins while ascending to the sky while voices say the same phrase in different languages, cancelling each other out until all that’s left is a hubbub in which no-one can distinguish anything anymore.

Like in many of the artist’s works, we are meant to apply different levels of interpretation to what we see. No-one truly knows where the remains of the tower of Babel are located. Another site now seems a more likely candidate, and we know that the one illustrated in nineteenth century engravings is not the right one. Late nineteenth century archaeologists, having discovered the ruins of the Borsippa ziggurat, which today looks like a ruined tower, assumed that they had found the remnants of the biblical edifice. However, the numerous engravings that exist of the twisted minaret of the mosque of Samarra could be the forerunners of our present-day idea of what the tower of Babel looked like. Popular beliefs often take over, even in terms of depictions. In which realm of the imagination did this particular belief take hold and how did it propagate? And to what end?

In the case of the war in Iraq just like for any war, among its causes are factors that are unknown to us that need to be identified and considered for better and more informed understanding. Knowledge of those factors, once gained, inevitably leads to the wholesale deconstruction of the respective roles of liberator and oppressed.

After all, isn’t history always written by the victors? So, when an artist who wasn’t a party to the conflict tells another story, doesn’t that deserve to be listened to too? Or at the very least viewed in a new light?

Léo Marin

[1] Borsippa is an ancient city of Mesopotamia. It is located at the site of today’s Birs Nimrud, around 20 kilometers south-west of Babylon.

MORE INFORMATIONS:

// Press release

// Louis-Cyprien Rials

// Fondation (09/22-12/15/2023 | Brussels)

// See also: Oyouni (09/09-10/21/2023 | Paris)

Category:

Exhibitions

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde_13

Louis-Cyprien Rials, exhibition views FONDATION, Galerie Eric Mouchet Brussels, 2023 © Hugard & Vanoverschelde_9