Oyouni – Louis-Cyprien Rials

Between Bagdad and Paris

16 May 2023

“The conduct of the Ancients must serve as a lesson to their descendants. May their fate be contemplated so as to learn from it. May the histories of the ancient peoples be learned so as to distinguish good from evil.” A Thousand and One Nights

Oyouni

After Révélation Emerige in 2015, after winning the SAM contemporary art prize in 2017, after his triple exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo, Dohyang Lee gallery and Galerie Eric Mouchet (2019), after winning the prix du 1% of Crédit Municipal de la Ville de Paris and after his exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, and most recently after a year spent in Iraq, Louis-Cyprien Rials now brings us two exhibitions at Galerie Eric Mouchet in Paris and in Brussels.

Oyouni (pronounced ayouni) literally means “my eyes”, but it can have additional meanings depending on the context. “With your eyes” you can say “I would give up my eyes for you.” Or to borrow a French expression: “you are dearer to me than the apple of my eye.” Louis-Cyprien Rials chose Oyouni as the title of his exhibition for quite a few reasons, including to reference the fact that it is his view as an artist that is developed and for the passion he feels for a country that inspired these two exhibitions after several other video projects.

Here he is at work using the eye of the artist to alert to the value of an external perspective on a culture buffeted and abused by the international geopolitical context and on a multi-faceted cultural identity undergoing constant reconstruction.

Aware that our image of Iraq is necessarily dictated by preconceived ideas coming from the media or views propounded by the propaganda outlets of one government or another, Louis-Cyprien Rials decided that the solution was to go to the country and dig and research and build his works up layer by layer.

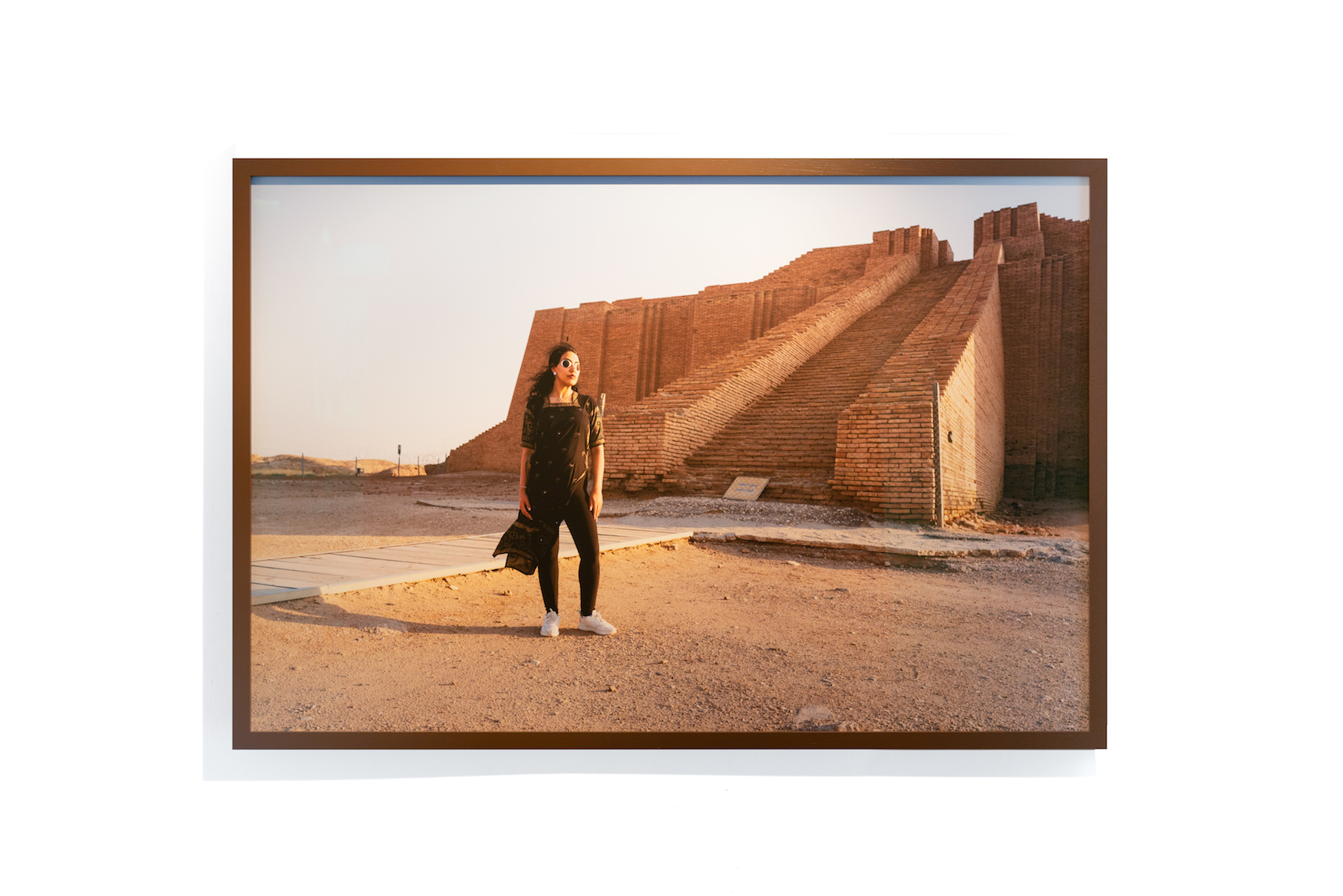

Louis-Cyprien Rials has always been fascinated by this part of the world, by the beauty of its landscapes and by the complex entanglements of religious and political influences constantly at play there. He crossed the border of Iraq for the first time by motorbike in 2011 and returned in 2015 to document Daesh’s persecution of the Yazidi [1] and Christians.

This backdrop is central to each of the works presented in this exhibition. It was when he came closest to the front line with Daesh that he filmed the Baba Gurgur oil field in Kirkuk. Mene, Mene, Tekel, Upharsin (2015), his first film shot in Iraq, features chants in Aramaic (the native language of Jesus Christ) mixed with the crackling sound and images of the perpetual fire from the Book of Daniel.

These new works are to be understood in the light of the artist’s ties to this region of the world. Iraq’s geopolitical variables are in constant flux. Nothing of the situation there can be understood from media sources alone. As soon as Iraq opened its borders to foreign visitors in 2021, Louis-Cyprien Rials made his way back to Bagdad, melded in with the local population, and began his observations again. He renewed contact with acquaintances from the past and continued working on projects whose outlines were already becoming apparent during previous exhibitions.

As he did with Beautiful Mogadishu, (2019), a work consisting of an ordinary T-Shirt emblazoned with the slogan Beautiful Mogadishu bought in the lobby of his secure hotel in one of the most dangerous cities in the world and presented in the exhibition Par la fenêtre brisée (Through the Broken Window) in 2019, with Le Caleçon de Daesh (Daesh’s Underpants) the artist employs irony to exorcise some people’s fascination for extreme danger and the adrenalin rush it produces, the monstrous, and the ways in which these can end up fetishised.

During his Introducing exhibition at Dohyang Lee Gallery in 2017, the artist emphasised the sacred nature of an ordinary woven Christian icon by carefully framing it, showing only its reverse side (No title). He brought it back from the town of Bakofa (Iraq), which was located on the front line between the so-called Islamic State and territory controlled by Kurdish Peshmergas [2] (2015). The town was previously home to a large Christian community, which was forced to flee or face extermination by a religious extremism that prohibited all visual representations of the sacred. Claiming they were stamping out ‘idolatry’, a grave sin for Islamic fundamentalists who reject any representation of ‘beings with a soul’, Daesh destroyed vast quantities of votive religious objects from all faiths. During subsequent visits to Iraq, Louis-Cyprien Rials continued collecting these forbidden woven icons, a large collection of which is proposed in the present exhibition. We only see their reverse sides. The front, along with the saint represented and the style of execution, remains hidden. Looking at the back, we can just about make out haloes and certain sacred attributes of Christ, the Virgin or the saints, done in gold thread. It is as though these abused and destroyed images survive only in the form of their spiritual aura. It serves as a metaphor for the West, which has averted its gaze and turned its back on the suffering of these minorities.

In an Iraq where a foundational, universalist and mythical past collides with a violent sectarian present, Louis-Cyprien Rials is not only on a quest for a universal truth but also striving for balance between his own demons and his idealism and fascinated to be located at the millennial navel of our very civilisation. As a voluntary exile from a hypocritical and toxic Western political climate and the nightlife of Paris and Belgrade, he has moved to a country where reconstruction is in full swing but where peace is fragile, to put it mildly. Like with the Aramaic prayer bowls he created previously for Révélations Emerige (2015), today he is drawing his background, traumas, and anxieties, and also the blessings he wishes for his near and dear, like in those bowls painted with mysterious characters entitled Sweet Demons that act as therapists or exorcists, whichever fits better. He is thus transmitting millennia old beliefs and rituals and showing that the ways in which humanity expresses its spiritual side has scarcely changed at all with the passage of time.

His film Oyouni uses Mesopotamian visual codes to present a series of portraits of Iraqis whose eyes are concealed behind larger eyes that are round and opaque and at the same time empty and full of life. These are large and mysterious 3D printed eyes like those created by Mesopotamian sculptors of the Sumerian period. They prevent us from seeing where the person wearing them is looking and they’re accompanied by Sumerian harp music and ancient Sumerian chanting. But they also show us which era these young people belong to and identify with. These are contemporary Iraqis, proud young people, whose Instagram profile names are written in cuneiform. Their motto is “Irak Wahed: One Iraq”. There can be no doubt that differences in political and religious convictions notwithstanding, these Iraqis are united by a single cultural identity dating back millennia, one inherited from ancient Mesopotamia. It is through these science-fiction hero eyes and through the perspective of the artist that we understand the value of the struggle for an identity. Their identity. His identity.

Like with his Sweet Demons reinterpretation of the ancestral bowls or the empty and yet expressive Sumerian eyes, created using vernacular techniques to express the timelessness of their spiritual message, Louis Cyprien Rials has also created new Afghan War Rugs. War rugs are carpets depicting current events made by Afghan carpet weavers using ancestral techniques for foreign customers, usually members of the occupation armies that have successively passed through the country. Far from offering windows into the everyday perspectives of the Afghan people, these works invite a more cross-cutting understanding than that conveyed by their iconography alone. The key to understanding them is to read between the lines.

Made to order for the artist by Afghan carpet weavers, they are the fruit of knowledge and skills dating back hundreds of years, but instead of depicting traditional lush garden scenes, they illustrate scenes of violence and murder. They include the voids left by the destruction of the Buddhas of Bamyan, a somewhat more classical – and more precise – depiction of the 9/11 attacks, and also poppy seed cultivation and an evocation of the fear engendered by the constant presence of drones flying over villages. The artist’s intention is to remind us, using a grating depiction of the Uzbin ambush, that following the Soviet and US invasions and at the same time as the Taliban was wreaking its own destruction on the country, France too sought to play its own moves on the great geopolitical chessboard that is Afghanistan and its mineral wealth.

In the manner of his previous work with Ugandan film studio Wakaliwood which under his supervision reinterpreted Japanese cinema’s monumental work Rashomon for his exhibition Sur la route de Wakaliga (On the Road to Wakaliga) (Palais de Tokyo – 2019), Louis-Cyprien Rials offers us the opportunity here to view a familiar story in a new light.

For we must not seek in the work of Louis-Cyprien Rials that which laziness accustoms us to see. It would be tempting to believe that weavers from a war-ravaged country on the other side of the world are sending us messages about the traumas they endure on a daily basis. We feign ignorance of the fact that it is Western carpet traders who are giving the weavers these ‘sensational’ new designs.

Afghan war carpets are produced to satisfy a market, just like any other souvenir. The customer is the American ‘saviour’, who needs to be flattered. These small sized war carpets were designed and produced to be sold to the troops occupying the country, just like war carpets before them were produced for Soviet occupation troops.

These War Rugs harbour memory. They are an indelible mark on both sides, and in them each side sees the evidence of its own victories.

By inventing new designs centred around events he cares about – France’s military presence in Afghanistan culminating in the Uzbin ambush and the poppy seed cultivation based economy that served as a backdrop – the artist challenges received notions about Afghanistan.

Louis-Cyprien Rials the critical political analyst sets here his own milestone in the contemporary history of the world. He offers a new perspective and brings us important news. He teaches us that the truth is never unequivocal and that a work should never be viewed in a ‘what you see is what you get’ perspective.

Léo Marin

[1] The Yezidis (Kurdish: Êzîdî / ئێزیدی) are an endogamous ethnic minority speaking mostly the Kurdish Kurmanji dialect, originally from Upper Mesopotamia. The majority of Yezidis remaining in the Middle East today live in northern Iraq, mainly in the Nineveh and Dohuk governorates. The Yezidi religion is monotheistic and goes back to the ancient Mesopotamian religions.

[2] Name given to Iraqi Kurdish fighters.

MORE INFORMATIONS:

// Press release

// Louis-Cyprien Rials

// Oyouni (09/09-10/21/2023 | Paris)

// See also : Fondation (09/22-12/16/2023 | Brussels)

Category:

Exhibitions

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_1

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_2

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_3

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_4

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_5

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_6

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_7

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_12

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_11

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_13

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_9

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_8

Louis-Cyprien Rials, vue d’exposition OYOUNI, Galerie Eric Mouchet, Paris, 2023. Photo Cyrille Robin_10